Donna Granata on the power of creativity and documenting an artistic legacy.

By Nancy D. Lackey Shaffer

Arts archive and library Focus on the Masters has been the steward for Ventura County’s artistic legacy since its founding in 1994. Through extensive research and documentation – interviews, photographs, recordings, magazine articles, reviews and more – it has amassed an invaluable collection of materials on many of the notable artists (in all disciplines and mediums) that call this area home. Few people live and breathe art so profoundly as FOTM founder Donna Granata.

Ventana Monthly had the opportunity to speak with Granata, who discussed the creation of the organization, the challenges it has faced, the value of art in society and more. (NOTE: This interview has been edited and condensed for space and clarity.)

VENTANA MONTHLY: Are you from Ventura County originally?

DONNA GRANATA: I was born in Encino, and spent a short period of my childhood in Garden Grove. My family moved to Camarillo while I was in the fourth grade. From there, at age 13, our family moved to Oak View. I fell in love with Ojai and Ventura and have remained here ever since.

What originally inspired you to found Focus on the Masters?

From my family to my closest friends, I have had the good fortune to be surrounded by artists my entire life. I studied art, art history and photography at Ventura College before transferring to the Brooks Institute of Photography to complete my undergraduate degree in commercial photography.

As I built a life as a photographer, I worked several odd jobs, teaching art classes, lecturing and waiting tables. One night in August 1994, while working at the Hungry Hunter in Ventura, I fell down a flight of stairs. During my year of convalescence, I tried to stay positive, focusing on what I could do within my physical limitations. I started organizing my photographs I had taken, as a student, of my friends that were noted artists including Beatrice Wood, David Leffel, Gerd Koch and Sergio Aragones, realizing they were more than simple portraits – they were historic documents. The more I pondered the images, I realized that they should be accessible historically. I thought to myself, why not start my own nonprofit arts archive and library?

Who was your first documented artist?

I started with photographer Horace Bristol because I was familiar with his work. He was an original LIFE photographer from 1937 to 1941. Among his seminal work are his Grapes of Wrath Series, World War II photographs (working under the great Edward Steichen) and images of post-war Asia. He lived in Ojai, and I hoped he would understand the concept of FOTM even though it still wasn’t fully formed in my mind. What began as a one-hour lunch meeting at his home turned into an all-day submersion into his history that lasted through a wonderful dinner. He and his wife Masako were so gracious and remained dear lifelong friends.

What was FOTM like in the early days?

In the early days, the documentation was quite simple, starting with cassette tapes and recording equipment I bought at a local thrift store. I enlisted friends and family to volunteer their talents, and our board members were very active in the day-to-day operations. The video recordings of the public interviews were recorded by Rex McBroom . . . These early recordings have since been digitized.

Prior to applying for our own non-profit 501(C)3, FOTM partnered with the Ojai Valley Museum as our fiscal sponsor. I converted my entire home in Casitas Springs into offices, a reading room and storage. In those early days, I sought the advice of Paul Karlstrom, former regional director of the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art and his staff. At the time the Archives of American Art had an office at the Huntington Library where one could make an appointment and study the files. FOTM’s collection methodology is modeled after the Smithsonian’s approach to documenting artists.

I joke, but it is true — when the files hit the ceiling, I hit the wall. After over 10 years operating from my home, FOTM moved to a suite of offices on Main Street in Ventura. From that point forward we grew exponentially.

Image courtesy of Focus on the Masters

In 2017, FOTM was headquartered at the Nonprofit Sustainability Center near Ventura City Hall – which put you right next to the flames of the Thomas Fire. How was FOTM affected?

The Thomas Fire affected us in so many ways — personally, emotionally and physically. My heart still aches for those who lost so much. FOTM’s offices have north-facing windows with a beautiful view of the Ventura Botanical Gardens. The fire devastated the gardens and burned across the city parking lot with flames licking our building and City Hall. FOTM suffered tremendous smoke damage. The air was so toxic in our offices that your eyes would water as soon as you entered the building. In addition to a professional cleaning crew, the City of Ventura provided two huge air purifiers to suck the pollutants out of the air. Each was the size of a refrigerator and sounded like a jet engine when they were turned on. It took several months to clean our offices. The only evidence the Thomas Fire left us is a crack in one of our windows.

Following the fire, FOTM assisted artists who lost their studios and work by providing “evidence of their worth” required for insurance claims. Among the ephemera we collect are digital libraries of the artists’ work, price sheets, exhibition history and a list of collections in which they belong. Priceless records for those who lost everything.

FOTM is in a new space now.

We have a very generous invitation from the Ventura County Community Foundation. We are still exploring the possibilities. FOTM has been working on succession and long-term planning for quite some time. It is one thing to be the founder of an archive and library, it is another to plan for it to flourish long after I am gone. The transition will be gradual, ensuring long-term stability. One of the most important aspects to our sustainability is a permanent home suitable to house our ever-expanding collection. We need a facility with proper storage, climate control, research space, offices and programming space. We need a facility that can expand as the archive expands and assist in partnerships to help disseminate our unique collection. VCCF is a promising facility and offers a bright and sustainable future.

How was FOTM affected by the pandemic?

FOTM implemented an emergency operating procedure right away. We froze all the expenses that we could and shifted our resources to our Learning To See Outreach in support of the schools and remote learning. Our Education Director, Aimee French, did a herculean job converting lessons to a Zoom format, developing art projects that can be downloaded from our website, and distributing individual art supply packets to the schools for parent pickup. The first year was very difficult as the schools tried to hold the students’ attention at the computer. In fact, the art lessons were an incentive for the students to tune in. By the end of the first year, teachers realized the importance of LTS as part of the curriculum.

As things have opened up more, has the organization been able to get back to its usual programming?

We are planning to be back to full programming in January 2023. Most of our volunteers are older and several are immune compromised. Our audience and our artists are mostly older as well. We have been very cautious trying to do our part to get past the pandemic.

Did FOTM stay in touch with its artists during the pandemic? What kinds of concerns were expressed during that time?

We did. The artists’ response to the pandemic varied. Some were extremely productive and grateful for the isolated time in the studio. Others had a complete creative block. Most devastating was the cancellation of exhibitions and performances. It is hard for people to imagine the work and the expense that goes into the production of a major show. It is devastating for those who could not reschedule. In many cases, artists prepare for years for a major exhibition. When they lose an exhibit, they lose more than prospective sales and the considerable expenses involved. They lose momentum and precious time preparing for the exhibit. They miss the joy of sharing their work with the public. In addition, the ripple effect goes out to all the supporting businesses as well.

Was FOTM able to document artists’ work during the pandemic?

Yes. For a visual artist, isolation is often a way of life. From the solitude of the studio masterpieces are born. Those who rouse the muse during challenging times can channel that energy and thrive creatively. But, there is more to the creative process than simply having the time to produce. It takes mind, body and soul. Inspiration strikes from the broad depths of emotion, from despair to great joy.

I interviewed six diverse artists during the lockdown: John Nava, Gary Lang, Ruth Pastine, Karen Lewis, Katie Van Horne and Kent Butler. It was so interesting to learn how the pandemic affected their studio practice. John Nava was the first to say, “….I didn’t realize how much my normal life pattern matched ‘lockdown.’”

Artists are authentic recorders of our collective history and humanity. They are the mirrors of society. In addition to the pandemic, many of the artists were responding to the overlapping political, social, economic and humanitarian crises unfolding at the same time. . . . An example of John’s socially conscious work can currently be seen in a five-artist show, The New Normal: Art and Politics, at Vita Art Center in Ventura through Nov. 2.

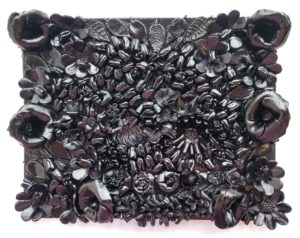

[Modernist painter Gary Lang] changed from his normally vibrant, energized color palette to a dark and somber tonality. Known for his signature pulsating massive circles, Gary had, during the pandemic, turned to painting concentric squares — confined, controlled and structured — as a way to make sense of a world out of control.

During the pandemic, [Lang’s partner] Ruth Pastine revisited works on paper and began a new series of hand-painted oils. The luminous color quality and dramatic palette was a surprise for the artist. She explained, “[T]he color and luminosity is really a gift right now because it’s filled with hope. It’s really helping to ignite and illuminate a much more positive emotional state.”

Tell us a little bit about your educational outreach program, Learning To See.

Among the odd jobs I worked in my college years was teaching art classes. I was one of the early teachers for Artist in the Classroom, a program now administered through the Ventura County Arts Council, that brought arts education into the schools during the severe budget cuts in the late 1980s and early 1990s. In fact, that is where I first met Aimee French, who also taught for Artist in the Classroom. During that time, I was also a docent at the Carnegie Art Museum. I was invited to participate in arts education training offered by the J. Paul Getty Museum called Learning To See. The skills I learned to engage the viewer with a work of art left a lasting impression on me. To this day, we still incorporate these techniques in our Learning To See Outreach and I still lecture on the J. Paul Getty collection.

Interestingly, Learning To See preceded the FOTM Arts Archive and Library. It is one of the reasons we are so dedicated to arts education. I feel so strongly that the arts need to be a part of the schools’ core curriculum. I believe the arts can be a path to peace. The more we understand our shared humanity, the more compassion is released into the world. Celebrating the diversity and uniqueness of our shared humanity is so important and needs to be taught from an early age. No two artists are the same. A celebration of individuality goes a long way to develop acceptance for and appreciation of different points of view, cultures and way of life.

What are some of the things Learning To See offers today?

Learning To See continues to evolve in response to the needs of the community. One of our current endeavors is the Impact Project, funded by the California Arts Council. The yearlong program is a celebration of the creative spirit by underrepresented communities in Ventura County. The project was led by the participants of the Black, immigrant and LGBTQ communities of Ventura County under the guidance and expertise of our education director, Aimee French. The program culminates in an exhibit at the Ventura County Government Center.

This exhibit is a testament to the value of individual and community expression. We asked, “What would you want to express as a member of an historically underrepresented community?” One of the immigrant participants was taken aback and stated that no one had ever asked her that question. Her reaction underscores the need for these types of community projects where lesser-seen points of view are illuminated.

Learning To See continues to reach thousands of students each year, keeping our seven faculty members very busy. Each lesson is inspired by the life and work of one of FOTM’s documented artists. Students apply themselves to their own art projects, gaining confidence and respect for themselves and others as they realize the rewards of creativity and concentrated endeavor. With an emphasis on critical thinking, social emotional learning, and innovation, art anchors them to a greater caring for our community and celebration of diversity.

How did you modify Learning To See during COVID?

Lessons were modified and new lessons were implemented to better support the social/emotional needs of students due to the pandemic. i.e. student focus and action seemed much slower, so more time was allowed for each lesson, emphasizing calming, physical actions of art over cerebral; and, when some students did not have their supplies on hand, we modeled resourcefulness and how to discover new, creative alternatives. Zoom provided a chance for frequent and meaningful interactions with classroom teachers. They communicated the need for their students to have an outlet in art and be involved with physical materials. Geoffrey Odell of Curren Elementary said, “My kids are starving for this type of activity.” Another shared that her students looked forward to art, which “sweetened the deal” for them to come back to school once they went into a hybrid model.

Looking back on all the years that FOTM has been tracking the area’s artistic legacy, what are some lessons that you have learned along the way?

Life can change at any given moment and the more adaptable one is to change, the better your chances of survival. The key is keeping your eye on what is most important. The community that we love and the qualities that unite us.

Throughout history artists tend to fall in and out of the public eye. Ranging from who is in vogue at the time to artists re-emerging posthumously, those who survive the test of time are artists who write or who are written about. Patrons of the arts, family members, art dealers and critics are often left with the task of championing the work and securing the memory of the artists. Artists can help to secure their own legacies by planning wisely while they are still here.

FOTM is building a bridge of primary source material for historians to follow. We unite a community of art lovers, patrons and educators providing the public with a firsthand opportunity to experience accomplished artists.

Focus on the Masters