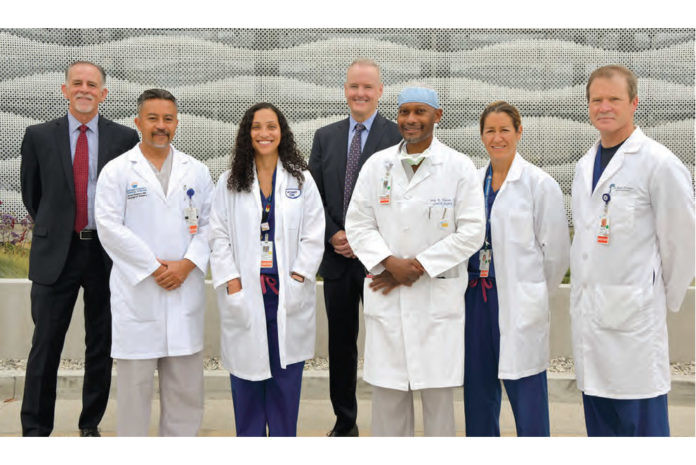

By Karen Lindell | Photos by Dina Pielaet

The team at the Ventura County Medical Center (VCMC) Trauma Center is like a NASCAR pit crew during the golden hour.

The mixed metaphor works, these medical professionals say.

Similar to a racing pit crew, every person on the Ventura hospital’s trauma team — comprising doctors of all kinds (surgeons, neurologists, anesthesiologists and radiologists, to name a few), nurses, EMTs, respiratory therapists, phlebotomists, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, physical and occupational therapists, social workers, dietitians, environmental service personnel — must work quickly in tandem, amid apparent chaos, using the utmost precision and skill.

And just like the first and last hours of daylight, when the sun’s warm, soft, diffused colors are ideal for photography, medicine’s golden hour after a traumatic injury is the first 60 minutes — the key period for emergency treatment.

This year, staff at VCMC are celebrating 10 years of the hospital’s designation as a Level II trauma center, the only such designated site in West County. Their never-ending race has the most golden of goals: saving human lives.

“Some people say ‘team’ and it sounds nice; at VCMC they live and breathe it,” said Mike Powers, CEO of Ventura County.

According to the California Emergency Medical Services Authority, the state’s 81 designated trauma centers admit more than 70,000 trauma patients each year; VCMC accounts for about 1,200 of those.

A decade ago, in June 2010, after debating for more than six hours, the Ventura County Board of Supervisors voted to name VCMC as the West County’s only Level II trauma center, edging out St. John’s Regional Medical Center in Oxnard. Both candidates were highly regarded; VCMC received a slightly higher score from the American College of Surgeons. A week earlier, Los Robles Regional Medical Center in Thousand Oaks had been named the East County Level II center.

The push to develop a coordinated trauma system in Ventura County had started many years earlier, and numerous people and institutions were responsible.

Among those who helped make it happen were two doctors from Anacapa Surgical Associates who are still part of the trauma team at VCMC: Thomas Duncan, D.O., trauma medical director; and Javier Romero, M.D., chair of surgery. At the Board of Supervisors meeting 10 years ago, they were part of the group advocating for VCMC.

But they prefer to praise anyone other than themselves for the county’s trauma system and its continued success, instead heaping praise on their colleagues.

“The ‘trauma center’ is the whole hospital,” Romero said. “Everybody participates, and everybody is affected. There is a trauma center team, but once the patient is admitted, care is hospital-wide. That’s the only way it works.”

Ventura County’s medical facilities certainly hadn’t been devoid of trauma treatment before 2010, but each hospital generally did its own thing.

Doctors, government officials and others had long wanted to create a system of coordinated care throughout the county. “It was very fragmented before then, dependent on individuals, not teams,” Romero said.

According to Duncan, in the past, when a trauma patient came into the ER, one surgeon and a resident got a call about a potential trauma patient. “Now, we come to the trauma bay in the ER as a bigger team, similar to a NASCAR crew. We have to take care of injuries in the golden hour — get them to the CT scanner, operating room or ICU — and respond to the highest level of care within 15 minutes.”

Traumatic injury is the primary cause of death for people ages 1 to 44 in the state, according to the California Emergency Medical Services Authority, including physical wounds from vehicle crashes, falls, burns, stabbings and gunshot wounds; trauma can also be emotional or psychological.

The different trauma center levels, which range from I (the highest designation) to V, refer to the resources available in a center and the number of patients admitted annually, according to the American Trauma Society.

Duncan explained that Level I “means you have a trauma team, cardiac bypass capability, a neurosurgeon in the house, surgery residents, and you do research.” At VCMC, he said, “We have everything Level I does except cardiac bypass capability.”

Trauma center designation occurs at the state or local level. Centers are then verified and evaluated by the American College of Surgeons (ACS). After an initial one-year verification, VCMC has gone through the process every three years, and passed each time.

Everything the trauma center does “is data driven,” said Romero, who became a doctor because he likes “scientific methodology; it’s very rational and algorithmic.”

Twice a year, VCMC receives “report cards” based on measures including mortality, morbidity, length of stay, palliative care and more. “It’s a very valuable tool we use to improve the way we deliver care based on the data,” Romero said.

During a trauma fellowship at USC, Romero learned about California counties that didn’t have trauma systems, including Ventura County, and decided to take a job at VCMC, hoping to be part of developing such a system.

“It took not only years, but administrative courage, to set up,” Romero said. “The county of Ventura and board of supervisors made a commitment to public safety. And that’s the real story: Nurses and doctors come and go, but the hospital remains, and the commitment needs to stay everlasting.”

Ventura County CEO Powers doesn’t have a medical background, but in 2010 served as director of the Ventura County Health Care Agency. As an administrator he championed the development of a countywide trauma system.

“The doctors and the nurses, their dedication and skill is really inspiring,” Powers said. And they don’t just care for injuries “on the back end,” he said. “They see the back end, and their mindset is to prevent it in the first place.”

Duncan is a major proponent of prevention. “The only thing more tragic than a death is a death that could be prevented,” he said. “A gun doesn’t go off on its own; a knife doesn’t stab on its own. Trauma is no accident; there’s a reason why these incidents happen. The ultimate goal is 0% preventable deaths.”

Duncan, who grew up in Nigeria and came to the US when he was 17, specialized in trauma medicine, he said, because “trauma is a way to save lives and provide preventive measures at the same time.”

He started or supports several trauma injury prevention programs in partnership with numerous organizations throughout the county.

For example, he helped start the Elderly Fall Coalition, a fall prevention program housed at the Ventura County Area Agency on Aging that offers classes and individual aid to people 65 and older.

According to the National Council on Aging, every 11 seconds, an older adult is treated in the emergency room for a fall; every 19 minutes, an older adult dies from a fall.

Stop the Bleed, developed by the ACS, teaches the public how to use tourniquets and gauze to prevent life-threatening bleeding.

VCMC also screens patients for domestic violence; works with law enforcement to help parents install car seats; offers helmets to those with injuries from bikes and other things with wheels; and participates in the Every 15 Minutes anti-drunk driving program at schools.

Duncan, who emphasizes that violence is a public health issue, also helped start a Violence Intervention program with the Ventura County Family Justice Center and other partners. Patients with injuries that are the result of violence are “seen by one of our counselors for that teachable moment at the hospital,” Duncan said. “We take advantage of bedside moments, instead of waiting to do it as an outpatient.”

Recently, the VCMC trauma team has faced a new complication: the coronavirus.

When a trauma patient arrives, the hospital team has to assume that person might have the coronavirus, so the staff all wear protective gear while treating that patient, and wait until they get the results of a coronavirus test before possibly changing that protocol.

Although the team has coped with memorable, newsworthy events like the 2015 Metrolink crash, most patients are treated for lesser-known traumatic incidents.

“I’ve been doing trauma for 20 years, and to choose a most memorable incident would diminish all the other ones I’ve treated,” Romero said. “Everybody is special and gets treated the same.”

Onofre Banderas of Ventura was treated by the VCMC trauma team in October 2019 after being struck in a random street shooting by someone with a shotgun while he was on Ventura Avenue. “If it wasn’t for the doctors being such professionals, I wouldn’t be alive, and some amazing nurses were really dedicated and helped me out through a tough time.”

Banderas was in the hospital for six months after the shooting; he’s still recovering, and can’t work due to his injuries, including a damaged arm and organs.

“Getting hit with a shotgun, it’s like a miniature grenade thrown into your body,” Banderas said. “I can’t explain the pain — just hot blood coming out of your body, knowing if you closed your eyes, that was it.”

And so another golden hour saved someone from darkness.