By Nancy D. Lackey Shaffer

Stephen Bates is perhaps best known as an expert on free speech, censorship and media politics. The graduate of Harvard Law School is a professor of journalism and media studies at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, where his research focuses on the First Amendment and, in particular, issues related to privacy, freedom of speech and of the press, the U.S. Constitution and First Amendment Law.

But when he’s not in Las Vegas, he can be found in Carpinteria, a place near and dear to his heart – and not just because of its beaches, beautiful weather and laid-back culture. His family history is intimately connected to the area; so much so that Bates Road is named after one of his relatives.

These days, Bates is taking a brief detour from his law studies to explore his family history and the role played by several generations of Bateses in the development of the Central Coast. He’s also working on a book (with local historian and Ventana Monthly contributor Vince Burns) about the history of Rincon Point.

Ventana Monthly caught up with Bates to talk to him about his illustrious relations, crossing paths with Ernest Hemingway, the history of Rincon Point and more.

You’re currently a professor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, but you spend a lot of time on the Central Coast. Did you grow up here?

I spent many summers at Rincon Point as a boy, but I was born in San Luis Obispo when my father was attending Cal Poly.

How are related to the Bates family of Rincon Point and Bates Road?

Robert Wentworth Bates, my grandfather, developed Rincon Point and ran the family’s Rincon del Mar Ranch from the 1920s to the 1970s. He had three daughters and one son who grew up there. The son was Robert W. Bates Jr., known in the family as Bobby. He was my father.

Do you still have relatives in the area?

The Rincon ranch is no longer in the family, but I have a few cousins nearby. Across the country, there are dozens of descendants of Josiah Bates, who came to the United States from England before the Civil War, but they have different surnames. My daughter Clara and I are the last of the blood descendants named Bates.

My understanding is that your great-grandfather, Dr. Charles Bell Bates, was an early doctor in Santa Barbara County. What brought him here?

His father, Josiah, was a London stockbroker who came to California in the late 1850s to oversee a troubled investment, a water company in the gold fields. In 1860, he summoned 18-year-old Charles to join him. Charles left his civilized life as a student at University College London for Gold Rush California, where he lived in a mountain shack and ate what he could kill.

After the water company failed, Charles went to medical school in San Francisco. He was eager to buy and sell real estate, and my impression is that medicine was simply a way to build capital. Supposedly he traveled down the coast and tried to figure out where Californians of the future would want to live. He thought the metropolis would be on the Central Coast, not in Southern California. He settled in Santa Barbara in 1869, practiced medicine, and invested in land. He was also president of the company that developed Montecito.

How did Rincon Point come into the family?

Dr. Bates practiced medicine in Santa Barbara with Mateo H. Biggs, a self-taught physician from Peru. Dr. Biggs was also keen to make money in real estate. He owned Rancho El Rincon, which extended along the coast from Carpinteria Creek in Carpinteria almost to Faria Beach — nearly 4,500 acres in Santa Barbara and Ventura counties. He sold about half of it piecemeal. Then in 1885, he sold the rest of it to Dr. Bates in partnership with Santa Barbara’s first pharmacist, Benigno Gutierrez. They each paid $5,000.

Gutierrez died in 1902, and his heirs sued to dissolve the partnership, possibly because they wanted to mortgage their share. Three court-appointed experts divided the ranch into two parcels of equal value. Dr. Bates got about 755 acres extending to the shore. The Gutierrez family got a bigger tract, 1,233 acres, in a more mountainous and remote area.

Dr. Bates, incidentally, seems to have had no sentimental attachment to the ranch. Before he died in 1911, he tried to sell it. He was putting his money into a Boston company that sold pianos on the installment plan. But nobody was willing to pay his price for the ranch, $25,000, so it stayed in the family.

What was it like to be a doctor at that time?

One day, a butcher on State Street slipped and fell onto his meat hook. Dr. Bates found the man lying on the ground, his intestines spilling out in the sawdust. He got a bowl of warm water, washed the intestines, poked them back into the abdomen, sewed the wound shut, and sent him home to die. When the butcher survived, nobody was more surprised than the doctor.

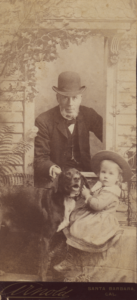

Dr. Bates was a fastidious English gentleman who liked to bicycle. He was a familiar sight riding through Santa Barbara on his bike, wearing a dark suit and a bowler, his shoes freshly shined, seated with ramrod-straight posture. When a little boy in town asked his mother where babies come from, she said Dr. Bates brings them in his bicycle basket.

Photo by Martha Stewart Photography

R.W. Bates, the son of Dr. Bates, drove an ambulance during WWI — alongside Ernest Hemingway! Did the two men know each other?

R. W. Bates, my grandfather, ran the Red Cross ambulance service in Italy, and Hemingway was one of his subordinates. Hemingway served on active duty for only a month before getting wounded. Captain Bates told him that the wounds were fairly minor, so he expected to see him back at the front soon. That may have irritated Hemingway. In any event, he never came back. He later reminisced in a letter about “what a sh*t Capt. Bates was,” but he also named one of his cats Bates, so maybe there was a modicum of affection.

Did the war affect R.W.?

Yes, deeply. He graduated from Harvard in 1911 and went to work for a piano company in Boston (the one his father had invested in). He planned to spend his life in New England. But he liked adventure, so he volunteered for the ambulance service. He found war horrifying yet invigorating. He felt that he lived more deeply during that time than during all his other years combined.

After the war, he decided he’d had enough of Boston and pianos. He married a French nurse named Juliette Marchand, who had treated him for appendicitis in Paris, and they came to Rincon Point and built a beach house.

Image courtesy of the Bates family

He became a farmer on the Rincon ranch. Was he successful?

No — I think it turned out to be harder than he expected. He nearly went broke trying to dry farm lima beans and hay. To make enough money to feed his family, he cured bacon and sold it door to door in Santa Barbara and Ventura. He finally got a job in Santa Paula selling real estate. He turned the farming over to a Japanese sharecropper named Kijuro Ota, whose crops were much more successful.

How did the name Bates Road come about?

In 1931, my grandfather built a ranch house on the mesa overlooking Rincon Point and moved his family there. His road intersected with the highway. In 1944, Ventura County put up a sign at the intersection, “Tubbs Road,” named after a judge who had farmed nearby.

My grandfather didn’t want to live on Tubbs Road. Whether he disliked Judge Tubbs or the sound of the word, I don’t know, but he didn’t want it to be his address. He called a Ventura County official and complained that it was a dreadful name. The official asked if he would prefer Bates Road. My grandfather said yes, that sounded much better.

I understand that you are writing a book about Rincon Point. What inspired you to take on that project?

I heard that a local writer, Vince Burns, was working on a photographic history of Rincon Point. I asked if he could use a coauthor, and he said yes. It has been a great opportunity to dig into the history of the area.

What surprised you in your research?

One minor thing resonates with me. Starting in 1912, people drove on wooden causeways near Rincon Point and La Conchita, with the waves breaking below. There’s a famous photo of Studebakers on one of the causeways.

In the mid-1920s, the county replaced the causeways with a regular road on fill, protected by a seawall. When the new construction was finished in 1927, the Ventura County Star said that it would soon be possible to drive from Ventura to Santa Barbara without any detours or construction delays — for the first time in two and a half years. Sound familiar?

family dog Nero. Photo courtesy of the Bates family

Your book will be published soon. What other projects do you have planned for the future?

I’ve been on sabbatical this year from UNLV. I’ll return to campus in August and get back to teaching and writing about journalism and law. I hope to continue writing about the history of the Central Coast on the side, for local publications as well as scholarly journals.

You split your time between Carpinteria and Las Vegas. What do you like about living on the Central Coast?

The area may have been just a money-making opportunity for Charles Bell Bates, but many of his descendants have seen it as much more. My grandfather found the place extraordinarily beautiful, and he considered himself lucky to live here. I agree.

Arcadia’s Images of America series will publish Rincon Point, by Vincent Burns and Stephen Bates, later this year. It can be pre-ordered on Amazon and elsewhere.

For more information on Stephen Bates, visit

www.unlv.edu/news/expert/stephen-bates.